How Anti-Asian Hate Crimes Impact AAPI Students

- In 2020, reported anti-Asian hate crimes increased 149%.

- Imprisonment of 120,000 Japanese people in the 1940s reflects a history of discrimination.

- The recent surge in anti-Asian hate intensifies mental health issues for AAPI students.

- The Stop Asian Hate movement works to dismantle systemic racism and improve equity.

People of Asian and Pacific Islander descent have lived in the United States for over 170 years. Violence and racism against the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) population also has a long history in the U.S., impacting individual and community experiences.

Nearly 11,500 hate incidents were reported to Stop AAPI Hate from March 2020-2022. The upswell of anti-Asian hate requires communities to address the impact on AAPI students nationwide.

History of Violence and Racism in the AAPI Community

Violence and racism against the AAPI community have a long history in the United States. Recent increases in reported anti-Asian hate reflect historical acts of discrimination.

In the 1850s, large numbers of Chinese people immigrated to the U.S. Working in the railroad construction industry gave rise to an idea that Asians were stealing American jobs. Government-supported discrimination and legalized anti-Asian practices began.

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 restricted Chinese immigration, denying citizenship and access to legal rights. The Immigration Act of 1924 excluded more immigrants, including a disproportionate number of Japanese citizens, making citizenship inaccessible until the 1940s.

The plague outbreak in 1900, in which Chinese people were blamed and forced into quarantine, holds similarities to anti-Asian sentiments presented during the COVID-19 outbreak.

During World War II, the imprisonment of nearly 120,000 people of Japanese descent — including American citizens — occurred in 10 camps across the United States.

After the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, violence and racism against the AAPI community increased. Hate crimes impacted South and East Asian communities in record numbers.

A report by the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism found that anti-Asian hate crimes increased by 149% in 2020. A history of violence and racism against AAPI people continues to impact communities today.

How Anti-Asian Hate Crimes Impact AAPI Students

In March 2021, eight people were killed in the Atlanta area — including six Asian women — at local spas. The crimes reflect a recent surge in anti-Asian violence across the country and highlight a need to address its impact.

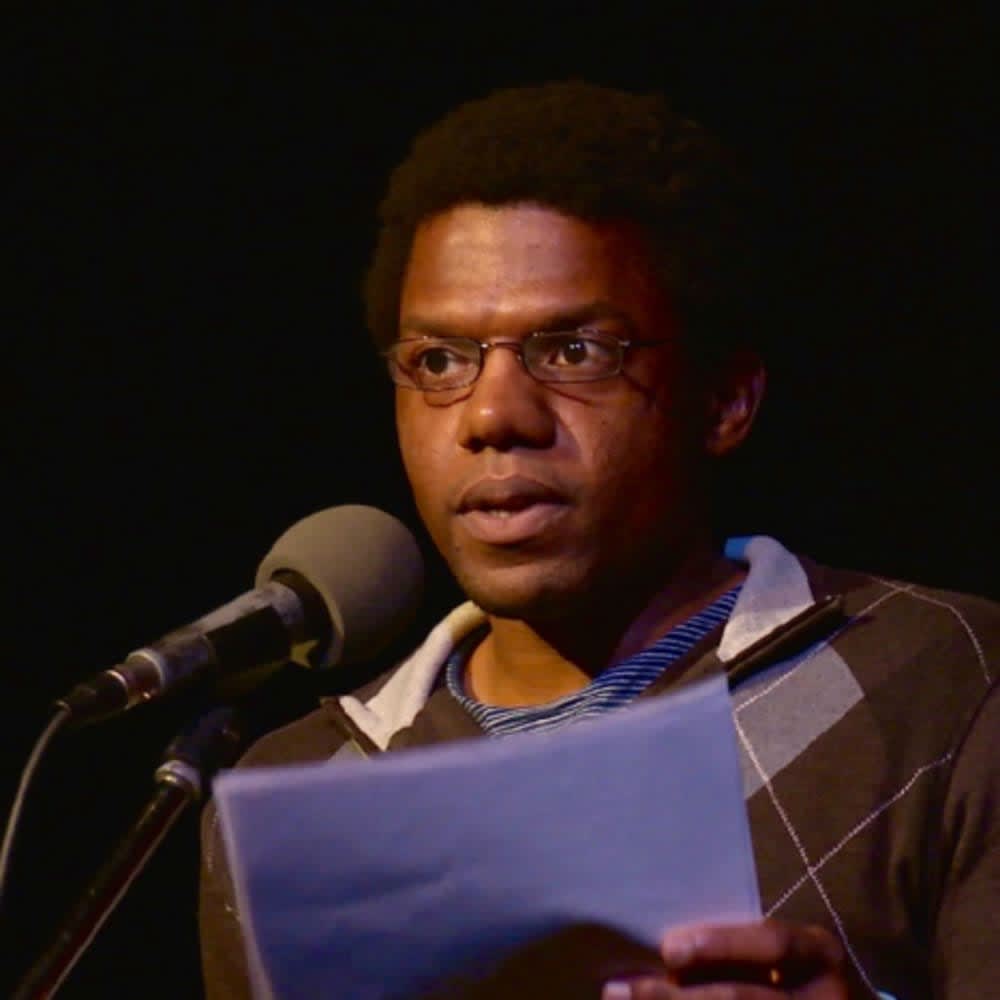

“For us college students, we fear for the future. We already harbor fears about employment. We fear a worsening economy, and we fear lack of opportunity,” Winston Yan, a third year political science student at the University of California, Santa Barbara, said. “Recent hate has only added to those worries. I remember my parents would call and tell me not to walk outside, not to go into places with too many people, in fear that I would be attacked or disparaged. When we can’t feel safe in our place of learning, how can we be expected to do our jobs as students?”

Asian Women Are Hypersexualized

Discrimination against Asian women — who are twice as likely to report that they’ve experienced targeted hate incidents — contributes to and results in part from the existence of a sexualized stereotype of them.

Psychological distress created by this bias can profoundly impact students’ mental health. Dax Valdes is a senior trainer and facilitator at Right to Be, an organization that provides bystander intervention and harassment-response training.

“As a facilitator, hearing stories of what attendees have gone through brings up a variety of emotions, including sadness and anxiety,” Valdes said. “There are a number of reasons for this, such as the pattern of hypersexualization that has been occurring toward Asian women since they arrived in this country and the global health situation with coronavirus (COVID-19).”

AAPI Communities Are Less Likely To Seek Mental Health Support

The AAPI community accesses mental health services at lower rates than other identity groups. This can leave some AAPI students without necessary mental health support.

The model minority myth — a perception that all AAPI people are submissive, hard working, and successful — can add to the impact of anti-Asian hate.

Stemming from anti-Asian immigration policies that identify success as a form of acceptance, the model minority myth can push students to ignore their own needs — instead focusing on socially expected norms of success.

Anti-Asian xenophobia is rooted in the historic oppression and discrimination of AAPI people. The impact over time leaves generations of families affected by trauma. Students may experience anxiety, depression, or sleep issues in relation to historic or current anti-Asian sentiments and violence.

The recent increase in anti-Asian hate crimes only exacerbates these feelings, heightening levels of distress.

What Is the Stop Asian Hate Movement?

The Stop Asian Hate movement arose in reaction to the swell of anti-Asian hate crimes in 2020. The Stop AAPI Hate coalition formed in March 2020 to address the discrimination and xenophobic hatred revolving around the COVID-19 pandemic.

Together, the AAPI Equity Alliance, Chinese for Affirmative Action, and the Asian American Studies Department at San Francisco State University built the Stop AAPI Hate organization that helped launch a movement.

Stop AAPI Hate works to dismantle systemic racism — discrimination, hate crimes, bullying, violence, and harassment — and improve equity for AAPI people in the U.S. The movement focuses on the need to end all forms of structural racism as a means to address anti-Asian racism.

AAPI students and others across the country can report hate incidents into an online database that tracks and responds to violence and racism. Stop AAPI Hate gathers data to report on racism and violence endured by all in the AAPI community.

The movement allows students across the country, from all AAPI communities, to unite in support and solidarity. Allies can contribute to the movement through protests, marches, and social media campaigns.

Resources to Address Anti-Asian Hate Crimes

Stop AAPI Hate: The organization behind the movement tracks and reports on anti-AAPI hate crimes and incidents nationwide. Their reports and resources provide insight and guidance for reducing racism against the AAPI community.

Stop Asian Hate: In line with the #STOPASIANHATE movement, Joey Ng created a database of news stories, practical resources for AAPI people, organizations to donate funds, and volunteer opportunities.

Virulent Hate Project: This research project studies anti-Asian racism and the impact of Asian American activism nationwide. The project discusses the impact of racism on individuals and communities and provides resources to help shape public policy.

Asian Americans Advancing Justice: AAJC raises awareness about racism and discrimination against Asian Americans. The organization provides resources and training opportunities on bystander intervention, standing up to harassment, and other ways to address anti-Asian hate.

#HATEISAVIRUS: This nonprofit works to dismantle racism and hate by building awareness and solidarity, educating on responses to discrimination, and raising money for Asian-led businesses. The organization empowers AAPI communities to stand up against racism — no matter who is impacted.

Addressing Anti-Asian Hate on Campus

Hate crimes against the AAPI population rose drastically in 2020. Incidents of violence, racism, and discrimination profoundly impact student communities. Addressing anti-Asian hate is critical for college and university campuses and the country at large.

Building awareness of anti-Asian discrimination and racism can help improve efforts of solidarity. Understanding how and when to intervene as a bystander, ways to safely report anti-Asian hate incidents, and the impact of xenophobia help build awareness and increase support.

The Stop Asian Hate movement provides a foundation of support and allyship that is essential to improving safe spaces for AAPI students nationwide.

“Solidarity is more important than ever,” Valdes said. “How can we stand together and support each other? Ignoring these situations is more difficult than ever. There is nothing new about these acts of bias, but it will take all of us to make a change — small acts of caring and intervention will eventually result in a major shift in culture.”

With Advice From:

Dax Valdes, a senior trainer at Right to Be, formerly Hollaback!, is an actor, choreographer, director, and teaching artist based in New York City. Currently, he is an actor with Only Make Believe — a nonprofit organization that creates and performs interactive theater for children in hospitals and care facilities. Valdes is also on faculty with the Art of Science Learning. He has served as associate artistic director for Leviathan Lab, education associate for the Vineyard Theatre, associate producer for the annual Career Transition for Dancers Galas (2004-2017), and producer for Capezio Dance Company’s 125th and 130th Anniversary Galas.

Valdes has also served as an associate member of the Society of Directors and Choreographers. He earned a BFA in musical theater at Point Park University and also attended Pacific Conservatory of the Performing Arts.

Winston Yan, a current third-year student at the University of California, Santa Barbara, is pursuing a major in political science and a minor in Asian American studies. He enjoys cooking, reading, hiking, and hanging out with friends. Taking from his college experiences, he hopes to move forward into more political activism, working for a government agency or a nonprofit.