Remedial Courses Are Failing Students. Can ‘Corequisite’ Education Help Them Earn a Degree?

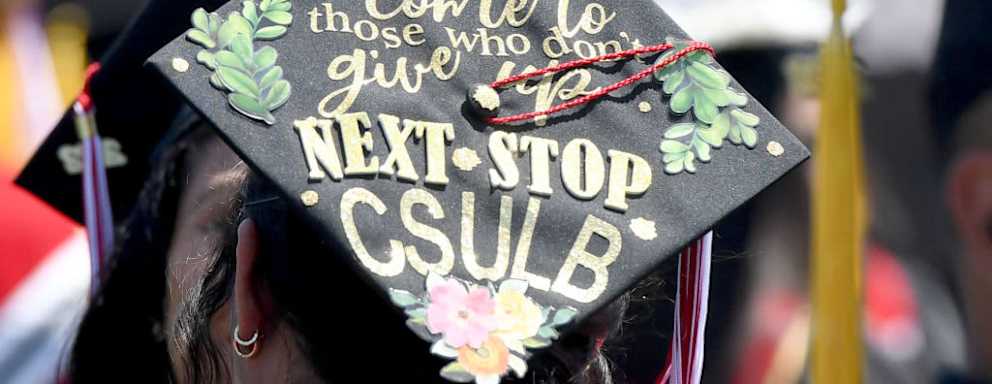

Credit: MediaNews Group / Long Beach Press-Telegram / Getty Images

Credit: MediaNews Group / Long Beach Press-Telegram / Getty Images- Forcing students to take remedial classes makes them less likely to complete gateway courses, research shows.

- Still, many college systems across the country utilize remedial courses.

- Many advocates are pushing for a new way to prepare students for math and English courses: corequisite education.

- This innovation helps students earn more college credit but often doesn’t translate to higher graduation rates.

Right now, thousands of students are taking college courses that won’t count toward their degree.

These students pay for the class just as they normally would, and the instructor’s syllabus may even list how many credits the class will earn them.

But those credits won’t actually count toward their diploma, and many experts believe the class won’t get them any nearer to graduation than if they would have skipped it altogether.

Welcome to the world of developmental — also known as remedial — education.

Stay in the Know!

Subscribe to our weekly emails and get the latest college news and resources sent straight to your inbox!

In short, developmental education programs are designed to get college students up to speed in subject areas like math and English. The institution, usually a community college, declares the student isn’t ready for college algebra so the student is placed in a warm-up class to better prepare them, for example.

Research suggests that while the intention is pure, in practice, these remedial courses only serve to drain money from students’ pockets without actually making them better at math.

Now, student-advocates are hoping a shift towards corequisite courses, in which struggling students can earn credit that counts toward their degree while receiving additional support to succeed in a class, can get students closer to earning a degree while also saving them money. But getting students over the finish line remains a challenge, whether they start their higher education journey in remedial or corequisite courses.

“(Remedial courses) are a dead end for so many students,” Amy Moreland, assistant vice chancellor of policy and strategy at the College System of Tennessee, told BestColleges.

Many, including Moreland, have spent the past 15 years trying to reform this commonplace practice. Still, disagreements surrounding the abandonment of remedial education have stymied widespread change. In some states, reforms have been rolled back to stick with the status quo.

States that have instituted reforms such as corequisite courses have enjoyed massive upticks in the percentage of students who complete college-level courses. However, those returns haven’t translated into increased graduation rates, making it harder to convince the powers that be that reform is worth the investment.

Still, many student advocates continue to push for what they see as much-needed change.

DEFINITIONS:

- Prerequisite remedial course: A college class that does not count toward a student’s credits needed to graduate, meant to prepare students for credit-bearing courses.

- Corequisite course: An alternative prerequisite course where students earn credit that counts toward their degree while receiving additional support to succeed in that class.

- Gateway course: A course that counts toward a student’s degree program.

A Long History of Developmental Education

Myra Snell is quite familiar with the remedial education system. In the early 2000s, she spearheaded developmental education programs in California that garnered her copious grant awards and recognition.

At the time, her community college offered four developmental math courses: arithmetic, pre-algebra, elementary algebra, and college algebra. Approximately 80% of students were placed in remediation, many of whom essentially had to redo all of their high school math studies for no college credit.

It seemed, at the time, like the best way to prepare students for college math.

“I did all kinds of things that I later worked hard to undo,” she told BestColleges.

Over the past 15 years, she’s advocated for undoing those policies after learning that just 6% of students placed in remediation ever completed a gateway class. Together with other researchers, she uncovered that students of color were impacted most by this practice.

Want to learn about college admissions? Read more:

“It was a ubiquitous, common pattern of attrition,” she said. “This was just the epitome of structural racism.”

Snell cofounded the California Acceleration Project in 2010 to help enact change across the state’s 72 community college districts. She was among the earliest people in U.S. higher education bringing attention to the inequities that remedial education exacerbates.

Tristan Denley was also among those early pioneers. Around the same time, he spearheaded a similar crusade in Tennessee but didn’t launch the state’s pilot program to weed out remedial courses until 2015.

He told BestColleges that before addressing the issue, only 15% of students who started in developmental math ever completed a gateway math course in Tennessee. Like in California, data ultimately spurred him to take action.

Inside the Push for — and Against — Reform

Those wanting to enact change were ultimately met with a dilemma: How do you cut remedial courses while also preparing students for college-level math, reading, and writing?

Amy Getz, senior program associate for mathematics education at WestEd, said corequisite education emerged as the best solution. Rather than force a student to take multiple remedial courses to prepare for a gateway course, the corequisite model places students directly into the gateway course.

But it doesn’t throw them into the deep end without support.

A student taking college-level algebra, for example, would take the course along with their peers. Under a corequisite model, the student would also take a learning support class to work more directly with faculty trained to bring students up to speed.

Research shows that a corequisite model leads to better outcomes for students than remedial courses.

A seven-year study by Trinity College and the City University of New York (CUNY) found that community college students typically finished their degree programs faster if they enrolled in corequisite courses instead of remedial courses. Additionally, they enjoyed $3,000-$4,500 more in earnings per year than students who were sent to remedial classes.

That data hasn’t made it easier for advocates, however.

“Once structures are in place,” Getz said, “it’s really hard to change them and give them up.”

There are a few reasons states, institutions, and individual faculty are hesitant to embrace corequisite programs.

For one, there is an overall lack of awareness. While data may clearly show that corequisites lead to more gateway course completion, Bruce Vandal of Bruce Vandal Consulting explained that it can be a challenge to get this data in front of decision-makers.

There’s also the issue of competing priorities. Community colleges have become hyper-focused on workforce development, so remedial education reform is seen as less important.

“[Workforce development] is not necessarily in contrast to these reforms,” Vandal said, “but in terms of where the priorities are, that’s the emphasis.”

Lastly, there can be more dubious reasons faculty don’t want to adopt corequisite reforms. If you eliminate remedial courses, what happens to the instructors who teach those courses?

“I don’t want to say that this is a prime motivation, but it certainly comes up,” Getz said.

That’s not to say there hasn’t been any progress.

Vandal said about half a dozen states have implemented comprehensive remedial education reforms and seen positive outcomes. Another 20-22 states, he said, have partial reforms, while about half the country has made no real progress on phasing out developmental education programs.

North Carolina is an example of a state that took steps forward, but then a few steps back.

Vandal explained that community college leaders reached an agreement in the early 2010s to eliminate remedial education. But without formal policies in place, those plans withered on the vine, and the agreement was eventually scrapped.

States like Ohio and Arkansas recommend corequisite support, he said, but it’s not a requirement.

“Do those recommendations work? No, they don’t,” Vandal said. “There’s really no evidence that that creates meaningful adoptions.”

Russ Deaton, executive vice chancellor for policy and strategy at the College System of Tennessee, said another hurdle is maintaining buy-in. The introduction of corequisite learning in 2015 led to immediate improvements, he said, but Tennessee needed to continue to make changes to flesh out the program.

For example, institutions needed to ensure faculty teaching gateway courses were in communication with those leading the learning support course.

“Our introduction of [corequisite] in 2015 vastly improved outcomes,” Deaton said. “But it was also version one; incomplete and not final.”

The Future of Corequisite Education

For all of the benefits of corequisite education, one obstacle remains: increasing completion rates.

Moreland explained that the percentage of students who passed a gateway course doubled after Tennessee instituted corequisite education. However, graduation and persistence rates have remained unchanged, showing that even though students are advancing to the next step in their educational journey, it doesn’t necessarily translate to reaching the finish line.

Tennessee is now experimenting with new ways to address this issue, she said.

Her department launched the Tennessee Coaching Project pilot program in fall 2022 at Jackson State and Northeast State community colleges.

The Coaching Project offers additional support for students placed into corequisite programs. Students are assigned an academic coach who helps them navigate coursework and utilize campus resources that can lead to higher success rates.

Preliminary results suggest the pilot program is working.

According to data from the Tennessee Board of Regents, 54% of fall 2023 students who engaged with their academic coach persisted through the next academic year, compared to 30% of students who were selected for coaching but did not engage.

Denley, now the deputy commissioner for academic affairs and innovation at the Louisiana Board of Regents, is also now looking to take the next step in addressing completion issues. In Louisiana, that comes through the Meauxmentum Framework.

“Coreq alone is an important step,” he said, “but it is not everything that needs to happen.”

The Meauxmentum Framework acknowledges that corequisite learning needs to be paired with other support systems. As part of this framework, corequisite reform is just one piece of a larger puzzle that includes:

- Simplifying choices available to students

- Designing efficient educational pathways

- Identifying curricular milestones that improve student success

- Deepening student engagement

Even within corequisite programs, however, there is room for improvement.

Vanessa Keadle, chief strategy officer at Student-Ready Strategies, told BestColleges that one major issue is that colleges don’t clearly state when a course is applicable to a student’s degree. This means students could accidentally enroll in optional, remedial courses that set them back in their timeline to graduate.

Institutions need to be clearer in how they label classes and not place the onus on students, she said.

“We need to think more about whether our higher ed institutions are student-ready instead of asking students to be college-ready,” Keadle said.

Snell said she believes the next big step in remedial education reform is in creating degree-specific gateway courses.

For example, does a communications major need to take the same math course as an engineering major? Or could there be a communications-specific math course that is more applicable to jobs in that field?

These reforms will continue to evolve, Denley said. There is no finish line for when progress can stop, and he shared a quote attributed to essayist and historian Thomas Carlyle to exemplify this point:

“Go as far as you can see; when you get there, you’ll be able to see further.”